Title: Differential Diagnosis of Intestinal Diseases: Distinguishing Between Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea, Pseudomembranous Colitis, Celiac Disease, Disaccharidase Deficiencies, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Abstract

Patients frequently present to gastroenterology clinics with overlapping symptoms of diarrhea, abdominal pain, and bloating, posing a significant diagnostic challenge. A precise differential diagnosis is critical for implementing effective treatment and preventing complications. This article systematically reviews the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnostic criteria for five common intestinal conditions: antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD) and its severe form, Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) or pseudomembranous colitis; celiac disease; disaccharidase deficiencies (e.g., lactose intolerance); and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). While AAD/CDI are typically linked to a disruption of the gut microbiota post-antibiotic therapy, celiac disease is an immune-mediated enteropathy triggered by gluten. Disaccharidase deficiencies result from enzymatic defects leading to osmotic diarrhea, and IBS is a disorder of gut-brain interaction characterized by chronic symptoms in the absence of detectable structural disease. The cornerstone of differentiation lies in a meticulous patient history, including dietary habits and medication use, combined with targeted investigations such as stool assays (e.g., for C. difficile toxin), serological tests (e.g., anti-tissue transglutaminase for celiac disease), breath tests, and endoscopic evaluation with histology. This review emphasizes a structured diagnostic algorithm to guide clinicians in accurately distinguishing these entities, thereby facilitating prompt and specific management strategies that range from antibiotic discontinuation and probiotic use to lifelong dietary modifications and neuromodulatory therapies.

Keywords: differential diagnosis, antibiotic-associated diarrhea, pseudomembranous colitis, celiac disease, lactose intolerance, disaccharidase deficiency, irritable bowel syndrome, gastroenterology

Introduction

Chronic and recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and bloating, are among the most common reasons for patient visits in primary care and gastroenterology settings (Ford et al., 2020). The differential diagnosis for this symptom complex is broad, encompassing conditions with vastly different etiologies, including infectious, immune-mediated, enzymatic, and functional disorders. Misdiagnosis can lead to ineffective treatments, unnecessary procedures, and patient distress. This article focuses on differentiating five key conditions: antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD), pseudomembranous colitis (caused by Clostridioides difficile), celiac disease, disaccharidase deficiencies, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Distinguishing between these entities is paramount, as their management ranges from simple dietary adjustments and medication cessation to lifelong strict gluten-free diets or targeted pharmacotherapy (Lacy et al., 2021). The objective of this review is to provide a clear, evidence-based framework for clinicians to navigate this common diagnostic dilemma.

Literature Review

1. Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea (AAD) and Pseudomembranous Colitis

Antibiotic-associated diarrhea is a common complication of antimicrobial therapy, occurring in approximately 5-35% of patients depending on the antibiotic class (Barbut & Meynard, 2022). While most cases of AAD are mild and self-limiting, a significant subset is caused by the overgrowth of Clostridioides difficile, which can progress to pseudomembranous colitis—a severe, potentially life-threatening condition. The primary pathophysiological mechanism of non-C. difficile AAD is a disruption of the normal colonic microbiota, leading to reduced fermentation of carbohydrates and osmotic diarrhea (Szajewska & Kołodziej, 2015). In contrast, C. difficile infection (CDI) is characterized by the production of toxins A (enterotoxin) and B (cytotoxin), which cause intense inflammation, mucosal damage, and the formation of pseudomembranes visible on colonoscopy (Smits et al., 2016). Key risk factors include recent antibiotic use, advanced age, and hospitalization.

2. Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is a systemic autoimmune disorder triggered by the ingestion of gluten in genetically predisposed individuals. The pathogenesis involves an immune response to gluten peptides that leads to villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and intraepithelial lymphocytosis in the small intestine (Lebwohl et al., 2018). This damage results in malabsorption, manifesting as chronic diarrhea, weight loss, bloating, and fatigue. It is associated with other autoimmune conditions like type 1 diabetes and thyroiditis. Diagnosis relies on a combination of serological testing, most commonly for immunoglobulin A (IgA) anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG) antibodies, and confirmation via histopathological analysis of duodenal biopsies (Husby et al., 2020).

3. Disaccharidase Deficiencies

Disaccharidase deficiencies are characterized by the inability to digest specific disaccharides due to a deficiency of the corresponding enzyme in the brush border of the small intestinal mucosa. Lactose intolerance, caused by lactase deficiency, is the most prevalent (Heyman & 2006). Undigested lactose passes into the colon, where it is fermented by bacteria, producing short-chain fatty acids, hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide, leading to symptoms of osmotic diarrhea, bloating, flatulence, and abdominal cramps (Misselwitz et al., 2019). Diagnosis is typically confirmed with a hydrogen breath test, though a diagnostic trial of a lactose-free diet is also common.

4. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

Irritable bowel syndrome is a functional gastrointestinal disorder defined by the Rome IV criteria as recurrent abdominal pain at least one day per week in the last three months, associated with defecation or a change in stool frequency or form (Palsson et al., 2016). Its pathophysiology is multifactorial, involving visceral hypersensitivity, altered gut motility, dysbiosis, disturbances in the gut-brain axis, and psychosocial factors (Enck et al., 2016). Crucially, IBS is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring the absence of alarm signs (e.g., weight loss, rectal bleeding, anemia) and the ruling out of organic diseases like celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease.

Materials and Methods

This narrative review was conducted by searching the PubMed/MEDLINE database and relevant medical textbooks for literature published between 2000 and 2024. Search terms included “differential diagnosis chronic diarrhea,” “antibiotic-associated diarrhea,” “Clostridioides difficile diagnosis,” “celiac disease pathogenesis,” “lactose intolerance,” “disaccharidase deficiency,” and “irritable bowel syndrome Rome criteria.” The search focused on human studies, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and clinical practice guidelines. Articles were selected based on their relevance to the diagnostic pathway and their contribution to understanding the distinct pathophysiology of each condition.

Analysis and Discussion

The clinical overlap between these five conditions necessitates a systematic diagnostic approach. The initial step is a comprehensive history and physical examination.

History and Symptom Analysis:

- Medication History: A recent course of antibiotics is the cardinal clue for AAD and CDI.

- Dietary Link: Symptoms clearly triggered by dairy products point toward lactose intolerance. Symptoms related to wheat, barley, and rye ingestion are suggestive of celiac disease, though this requires serological confirmation.

- Symptom Pattern: IBS is characterized by a chronic course (fulfilling Rome IV criteria) and a frequent association between abdominal pain and bowel habits. The presence of “alarm features” such as unexplained weight loss, nocturnal diarrhea, or rectal bleeding strongly argues against a diagnosis of IBS and mandates investigation for organic disease like celiac or CDI (Lacy et al., 2021).

Diagnostic Testing:

The diagnostic journey often begins with the most common and easily testable conditions. For a patient with diarrhea, initial tests should include a complete blood count (CBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), and celiac serology (IgA tTG) to screen for inflammation and celiac disease (Ford et al., 2020). If there is a history of antibiotic use, a C. difficile stool toxin test is imperative. A positive test confirms CDI, directing treatment with antibiotics like vancomycin or fidaxomicin. A negative test in the context of antibiotic use suggests non-C. difficile AAD, which is managed supportively, potentially with probiotics.

If celiac serology is positive, the diagnosis must be confirmed with a duodenal biopsy while the patient is on a gluten-containing diet. The finding of villous atrophy is diagnostic, and management involves a strict, lifelong gluten-free diet (Husby et al., 2020).

For patients with negative initial workup and a strong dietary link to dairy, a hydrogen breath test can confirm lactase deficiency. A trial of a lactose-free diet with symptom resolution is both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Only after these organic causes have been confidently excluded should a diagnosis of IBS be considered. The positive identification of a symptom pattern consistent with the Rome IV criteria, in the absence of alarm features and with normal basic investigations, allows for the diagnosis of IBS. Treatment then focuses on diet (e.g., low FODMAP diet), stress management, and medications targeting pain and altered bowel habits (Lacy et al., 2021).

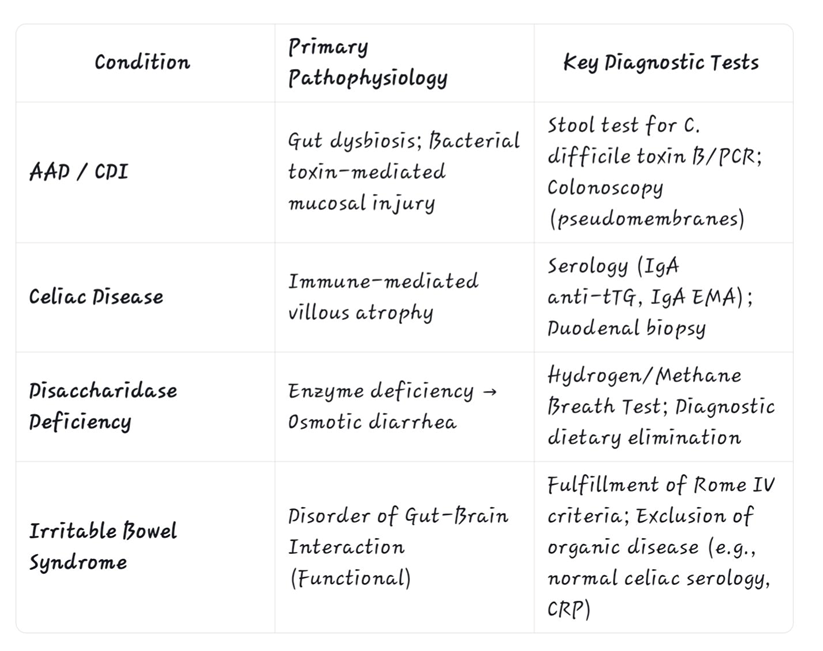

A targeted Investigative approach is essential for differentiation,as outlined in the table below.

Table 1: Key Diagnostic Features for Differentiating Intestinal Diseases

Conclusion

The differential diagnosis of intestinal diseases presenting with diarrhea, pain, and bloating is a common clinical challenge. A systematic approach is vital for accurate diagnosis and effective management. The clinician must first elicit a detailed history focusing on medication use, dietary triggers, and symptom patterns. This should be followed by a logical sequence of investigations to rule out organic diseases: stool studies for C. difficile, serology and biopsy for celiac disease, and breath tests for disaccharidase deficiencies. Irritable bowel syndrome remains a diagnosis of exclusion, made only after these other entities have been thoroughly investigated and ruled out. Adherence to this structured diagnostic algorithm ensures that patients receive timely, specific, and effective treatments, thereby improving clinical outcomes and quality of life.

References

Barbut, F., & Meynard, J. L. (2022). Managing antibiotic-associated diarrhea. BMJ, 376, e067248.

Enck, P., Aziz, Q., Barbara, G., Farmer, A. D., Fukudo, S., Mayer, E. A., … & Spiller, R. C. (2016). Irritable bowel syndrome. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2, 16014.

Ford, A. C., Moayyedi, P., Chey, W. D., Harris, L. A., Lacy, B. E., Saito, Y. A., & Quigley, E. M. M. (2020). American College of Gastroenterology monograph on management of irritable bowel syndrome. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 115(1), 1-28.

Heyman, M. B., & Committee on Nutrition. (2006). Lactose intolerance in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics, 118(3), 1279–1286.

Husby, S., Koletzko, S., Korponay-Szabó, I., Kurppa, K., Mearin, M. L., Ribes-Koninckx, C., … & Shamir, R. (2020). European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 70(1), 141-156.

Lacy, B. E., Pimentel, M., Brenner, D. M., Chey, W. D., Keefer, L. A., Long, M. D., & Moshiree, B. (2021). ACG clinical guideline: Management of irritable bowel syndrome. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 116(1), 17-44.

Lebwohl, B., Sanders, D. S., & Green, P. H. (2018). Coeliac disease. The Lancet, 391(10115), 70-81.

Misselwitz, B., Butter, M., Verbeke, K., & Fox, M. R. (2019). Update on lactose malabsorption and intolerance: pathogenesis, diagnosis and clinical management. Gut, 68(11), 2080-2091.

Palsson, O. S., Whitehead, W. E., van Tilburg, M. A., Chang, L., Chey, W., Crowell, M. D., … & Spiegel, B. (2016). Development and validation of the Rome IV diagnostic questionnaire for adults. Gastroenterology, 150(6), 1481-1491.

Smits, W. K., Lyras, D., Lacy, D. B., Wilcox, M. H., & Kuijper, E. J. (2016). Clostridium difficile infection. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2, 16020.

Szajewska, H., & Kołodziej, M. (2015). Systematic review with meta-analysis: Saccharomyces boulardii in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 42(7), 793-801.